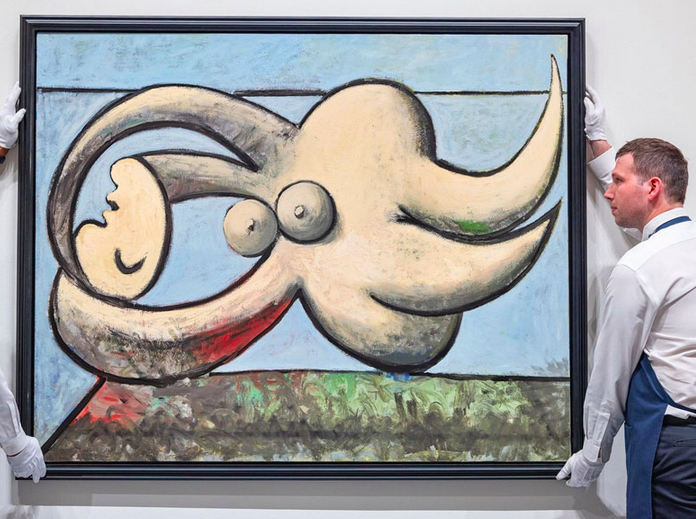

The Picasso-Matisse (or Matisse Picasso) exhibition opened at the Tate Modern twenty years ago, running for three months before traveling to Paris, finally making it to New York’s MOMA in early 2003.

It was a landmark event in many ways, a massive installation that set the pace for other comparative exhibits in the years to come. About half the shows put up in the new Whitney, I’ve noticed, are not for individual names but for the works of two, three, four, five artists who are ostensibly of the same school or sensibility. This actually follows the Whitney’s own long experience in maintaining a friendly and familiar Permanent Exhibition of 20th Century American art. Which was the only consistently good exhibit.

At least they used to maintain it up on East 74th Street, where it took up a whole floor. When I visit their new digs in the Meat Market, they always seem to have most of their nice pieces put away in storage, to make way for yet another fingerpainting show by savage pygmies.

I attended the Tate Modern show in its press preview days, and brought back the press kit, and the PR blurb which I’ve scarcely looked at (see below), and a souvenir pin-back button.

Also bought a mug at the gift shop. The mug soon lost its handle, but still sits on the shelf there, full of pencils and brushes and implements of destruction.

A couple of snippets from the Tate’s opening press release:

Matisse and Picasso are the acknowledged twin giants of modern art, between them having originated many of the most significant innovations of twentieth-century painting and sculpture. This major exhibition explores their relationship, which is revealed as much closer and more complex than has been thought. In spite of their initial rivalry, each came to acknowledge the other as his only true equal. In old age they became increasingly close personally, and increasingly important to each other artistically.

* * *

From 1906 to 1917 there was open rivalry between the artists. This was a time of intense innovation, when between them they produced some of the greatest art of the twentieth century. This period forms the densest part of the exhibition. Among the revelatory pairings are Picasso’s monumental Boy Leading a Horse of 1906 and Matisse’s Le Luxe l of 1907; Matisse’s celebrated Blue Nude and Picasso’s relatively little known, aggressively primitivist Nude with Raised Arms, both of 1907; and, in a stunning sequence of paintings of women, Matisse’s great portrait of his wife of 1913 and Picasso’s majestic Woman with a Fan of 1908. Other sections are devoted to still life and landscape. A key section shows Matisse responding to synthetic Cubism in his Moroccans, 1915-16, and Piano Lesson, 1916. Picasso in turn responded to Matisse’s interpretation of Cubism by producing a new, more decorative Cubism of his own, as for example in Three Musicians of 1921.